How Might We... Prototype Services Better

By Alistair Ruff, User Centred Design Lead at PDR.

Design is increasingly being called into action across broader spheres, designing services, strategies, policies, transformations, communities, or organisations. These all come with their own challenges and the application of the design process to these fields should be done in an appropriately reflective way. I’m aiming to identify some opportunities for design to develop its practice here, the current is not always bad, but the future could be better.

Why service design?

I’ll be using ‘service design’ as a catch all term for describing the application of design to these complex arenas. The definition of service design I won’t tackle here, many others have already done this. So why not strategic, policy or experience design, etc? I think Lucy Kimbell put it best:

Only service design maps directly onto established categories within economics which divide up activities into the extraction of raw materials, manufacturing, and services.

Lucy Kimbell

This consideration of services in economic & market terms, previously primarily the domain of ‘service marketing’, is gaining traction within the design community. And I think rightly so, if we seriously intend design(ers) to have an impact at a business level, we must be able to communicate at that level. Matt Edgar’s recent blog post on what he means when he talks about services is a good example of this.

This resonated with my research, tracing the roots of how we talk about services in design currently, and how we can move this forward. In service marketing, the concept of service-dominant logic and value co-creation have been developing since Vargo & Lusch first proposed it in 2004. However, the practice of service development was still based in a value-in-exchange model as opposed to value-in-use. In effect, organisations were designing and selling services with a product development approach, attempting to embed value into a service and sell that value in a transaction.

Staff from the Latvia Public Service experimenting with role play and digital prototyping techniques.

Is this design’s opportunity?

In my experience of applying the design process to business and organisational challenges, the two most fundamental differences when using a design process instead of other service development approaches is the inclusion of ongoing user research, and an iterative prototyping process. Both methods are used to identify how a service can and will provide value to people in use. Yu & Sangiorgi’s 2018 paper agree that a design approach fills the gaps in new service development, allowing organisations to design with an understanding that the value of the service is not embedded by them and delivered to people, but co-created with these people.

Prototypes externalise the proposed future service in a way that allows those outside of the design team to experience and shape the service in development. When an organisation moves to recognise that value is co-created with others, prototyping services in a way that they can be experienced by people is a key component in identifying whether the services do provide the intended value.

However, when it comes to prototyping ‘intangible’ services, there is an inevitable uncertainty. Can you accurately represent services that rely on the passage of time, human relationships, multiple physical environments, and mobile technology in a prototype? And should you try? We have some strong methods and thinking already in this space, I often refer back to Roberta Tassi’s Service Design Tools for example. But other design practices have much more developed prototyping practice and can point us in the right direction for developing service design.

Borrowing prototyping theory

Arguably what most people think of when they think of prototyping is products; prototypes you can pick up or walk around. In product design we know that prototypes can have different purposes:

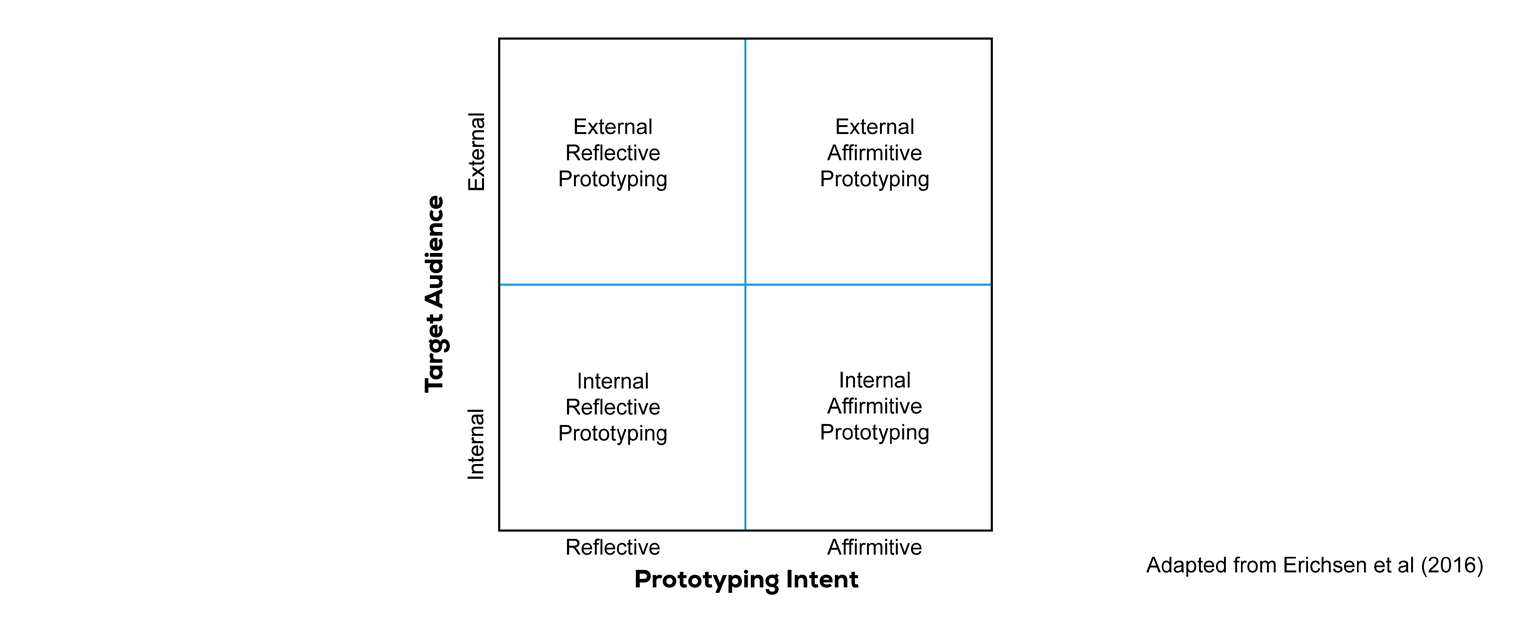

A model of four prototyping categories (Erichsen et al. 2016)

Erichsen’s model from the automotive industry recognises that not all prototypes are for the same purposes, therefore not all prototypes need to be planned in the same way, or with the same degree of accuracy or fidelity. One thing in particular worth noting is that not all prototypes are for external audiences, and not all prototypes are for ‘testing’.

If we really want to dig into prototype theory, Interaction Design or HCI is the place to look. Lim and Stolterman’s ‘Fundamental Prototyping Principle’ is a great summary of this understanding:

Prototyping is an activity with the purpose of creating a manifestation that, in its simplest form, filters the qualities in which designers are interested, without distorting the understanding of the whole.

Youn-Kyung Lim and Erik Stolterman

Designers should plan prototypes based on what they want to learn. They recognise how being economical with time and materials can enable them to achieve these aims, without destroying the audiences grasp of the overall design. This idea of prototypes having various ‘qualities’ that can be manipulated to the designer’s own ends is developed through McCurdy et al’s ‘mixed fidelity’ model. They propose various dimensions of fidelity that can and should be controlled for the prototypes intended purposes. In Interaction Design/HCI They identify the following 5 dimensions:

- Level of visual refinement

- Breadth of functionality

- Depth of functionality

- Richness of interactivity

- Richness of data model

If you’re like me, seeing this written down for the first time was such a clear articulation of everything I’d come to understand about building interactive digital prototypes, sparking my desire to investigate it further. Specifically, my research will be looking to uncover what might be the 5 dimensions of fidelity to consider when we prototype services.

What is clear is that there is no one approach to prototyping that can satisfy all needs within service design. Prototyping an end to end service will inherently differ from the prototype of an individual touchpoint along that service journey, the designer needs to recognise this and control the qualities of the prototype to achieve their aims. Recognising this level of control we can have and consciously planning prototypes based on it, is the first step to better service design prototyping.